SMOKING OR NON-SMOKING? The bizarre story of cremation in Britain

The story of modern cremations in Britain begins on 8 July 1822, and a storm at sea, a small boat, and its passengers, Edward Williams and the handsome young poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Watching from the shoreline of the Gulf of Spezzia, their friend Edward Trelawney saw with sinking heart how the Italian sky darkened and lowered, embracing the vessel in a squall from which it would never emerge. The dead poet’s body was found on the beach near Viareggioten days later and here his distraught friends assembled and, in a grand, drunken, momentous gesture, they built a pyre and burned their friend’s bloated corpse to ashes.

Their desire to cremate Shelley would have been immediately comprehensible to the Ancient Greeks, whose funerary customs Byron and his friends consciously aped, to many other denizens of the ancient world, and many modern ones outside Europe, from the Hindus to the Digger Indians of Utah – though the latter’s habit of mixing the ashes with gum and smearing them on each other’s head were probably unique. Others, though, from the Chinese to the Ancient Egyptians regarded cremation as barbarous, and preferred to bury their dead. So too did the Jews, for whom body burning was reserved for undesirables and sinners.

By extension, Christianity inherited an abhorrence of cremation- except for the likes of witches and heretics – strengthened by the belief that the corpses of the righteous would arise on the Last Day. Thus, the funeral pyres of Roman Britain were replaced by ‘six-feet under’ and a steady job for generations of gravediggers. But as the population expanded, pressure on churchyards led to the opening of massive municipal cemeteries, unhealthy at the best of times, prey to 18th century body-snatchers and breeding-pits.

It was concerns of this sort which, in 1869, 47 years after Shelley’s death, prompted two Italian professors called Castiglioni and Coletti to advocate a return to cremation at the Medical International Congress at Florence. As cremation turns 97% of the body to gas, which returns to the environment within hours, and completely destroys any diseases, contagious or otherwise, it had to be a better bet than burial. Their views were shared by Professor Brunetti of Padua who developed a functional cremation chamber, which he displayed at the Vienna Exhibition of 1873. It was thus that cremation first fired the enthusiasm of an idealistic 33-year countryman of Shelley’s called Henry Thompson.

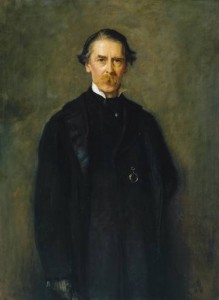

Sir Henry Thompson, pioneer of cremation in Britain

Thompson, of 35 Wimpole Street, London, was the son of a general dealer from Framlingham, Suffolk. A talented writer and painter, a bon-viveur who enjoyed hosting eight course dinners for eight people called ‘octaves’ and, primarily, a surgeon. Specialising in removing bladder stones, he operated successfully on King Leopold I of Belgium and also treated Napoleon III, in 1873. The course of three operations, performed at Chiselhurst, progressed successfully until, an hour before the third was due to start, the exiled emperor collapsed dead.

The Emperor was buried in cold splendour at Farnborough, but thenceforth Thompson was obsessed with one thing – cremation. Within the year he had developed his own cremation device with a reverberating chamber which could reduce a body treated with water, carbonic acid and ammonia to 4lb of lime dust in under an hour, and published an article advocating cremation as a ‘necessary sanitary precaution against the propagation of disease’, in the Contemporary Review. His proposal that the ashes could make a good fertiliser were perhaps a little unwise, and his views certainly prompted controversy. A fellow surgeon, Sir Francis Seymour Haden, whose advocacy of burials included plans to introduce papier maché coffins, countered Thompson with A Protest Against Cremation (1875) and, later, Cremation an Incentive to Crime (2nd ed. 1892), arguing that burning bodies could expunge forensic evidence of murder.

To Thompson’s defence leapt the dwarf-like Hugh Reginald Haweis (1838-1901), a virtuoso violinist – he had been taught by a pupil of Paganini’s – and progressive Anglican clergyman who advocated Sunday openings of museums and galleries, use of disused churchyards as public gardens and, now, cremation. His Ashes to ashes, a cremation prelude was published in 1875. But Thompson had already gathered powerful friends and, at a meeting at his house in January 1874, attended by the likes of Trollope, Millais and Tenniel (illustrator of Alice in Wonderland) he founded the Cremation Society, the first of its kind in Europe, and was elected its president. The Society proceeded to buy a plot near Brookwood Cemetery in Woking,Surrey, built a crematorium and, in 1879, assisted by the Italian Professor Gorini, Thompson successfully cremated a large horse. The stage was set but, although nobody could find anything on the statute books to prove cremation was illegal, the Home Secretary bowed to pressure from many sources, not least the alarmed inhabitants of Woking, and forbade any human burnings.

And that could have been the end of the story, but in 1882, while Thompson smouldered, a Dorset gentleman, Captain Thomas Hanham, RN, took matters into his hands. Assisted by a relative, John Castleman Swinburn-Hanham, he built his own furnace at Blandford and cremated his wife (dead since 1876) and mother (dead since 1877)- and the Home Secretary did nothing. Then, in 1884, an 82-year-old Welsh Hugh Driud, Dr William Price, cremated the body of his dead five-month-old son, called Jesus Christ Price.

Price was arrested and tried, but the judge could find nothing illegal in what he had done and released him. Price claimed damages for wrongful arrest and was awarded a farthing. The same year, a bill to impose regulations on cremations failed due to Government and Opposition objections, but the bill’s failure to become law did not mean cremation was illegal, and Thompson felt it was time to act.

A leading light of the London literary scene, Mrs Pickersgill, recently deceased and passionate about Thompson’s cause, followed the Hanhams, Jesus Christ Price and the horse by being cremated in Britain, at Woking on 26 March 1885.The same year saw two more cremations at Woking, Mr Charles Carpenter and a 14-stone woman who took an hour and a half to become ash.

Thompson published his Modern cremation, its history and practise in 1889, and the book’s success engendered a steady rise in cremations. Many still viewed it with suspicion, but amongst those who advocated cremation, it was treated as a passionate cause and a great cleansing and civilising influence in Victorian society. Amongst its wealthy advocates were the Dukes of Westminster and Bedford. Fabulously wealthy, they lavished out money to build a Gothic waiting room and a room for religious services at Woking. A dedicated hypochondriac, Bedford waited until the additions were complete in 1891 and promptly shot himself, contributing to the statistic of 1,842 people to have been cremated there by 1900, to which were added, amongst others, in 1901, the dwarf-clergyman Hugh Reginald Haweis.

Not content with Woking, the Cremation Society encouraged the opening of crematoriums elsewhere. Manchester crematorium, founded by a branch of the Cremation Society, opened its fiery portals in 1892, followed by similar enterprises in Glasgowin 1895, Liverpool the year after and Darlington in 1901. Beyond the seas, Thompson’s ideas alighted enthusiasm in countries as far afield as the United States and Japan. 1901 also saw an important development with the opening of Hull crematorium, the first to have been opened not by a private society, but by a municipal council. 1902 saw the first piece of cremation legislation, the Cremation Act, pass relatively smoothly through Parliament, and also the opening of the second municipal crematorium, in Leicester.

But the most important crematorium of all, to which cremation enthusiasts throughout the world look to for inspiration, was Golders Green. Built by the London Crematorium Company Ltd, founded specially by Thompson, the crematorium was designed by the revered country house architect Sir Ernest George, RA, and catered for north London. The furnace was stoked up in November 1902, with none other than John Castleman Swinburn-Hanham as managing director.

Sir Henry Thompson, baronet, as he had now become, had the happiness of opening further crematoriums, such as the one in Birmingham in 1903, before dying on 18 April 1904. The cremation took place at Golder’s Green on 21st. There can have been few occasions in history when a funeral represented such a literal triumph on the part of the deceased. By the very act of having his body reduced to gas and ash, Thompson had achieved what he had spent half his life fighting for. He was the 4409th person to be cremated in Britain since he had pioneered its re-introduction. If you are interested, you can still see his bust at Golders Green now, looking dignifiedly self-satisfied.

The numbers of crematoriums grew steadily. There were 13 in Britainby 1906 and 16 by 1926 – the numbers go on. The first Welsh crematorium was opened in Pontypridd in 1923 and the first in Northern Ireland at Crossnacreevy in 1961. Queen Victoria’s daughter-in-law the Duchess of Connaught became the first royal crematee in 1917; Sir Henry Irving the first cremated person to be interred in Westminster Abbey (and soon, strapped for space, the abbey insisted on cremation for its internees); Dr Temple was the first Archbishop of Canterbury to prefer burning to burying in 1944, followed the next year by Cosmo Lang, who had been archbishop before him. The following year saw H.G. Wells go up in smoke as well.

In 1959, Manny Shinwell unveiled a Jewish Scroll of Remembrance at Golders Green, indicating the final approval of the Reform and Liberal Synagogues. But a more formidable bastion of anticremationism was the Catholic church. In 1886, faced with the alarming prospect of the voluntary combustion of English Catholic bodies after death rather than the more traditional form of them being burned at the stake by Protestants, the Pope banned cremation, universally, on pain of excommunication. The only Germans excommunicated throughout the whole dismal episode of the Second World War were a handful who stood up for cremation.

But even Popes have to bow to public opinion and, in 1963, Catholics were given the green-light, provided the funeral service was conducted while the body was still intact (that rule has recently been relaxed): three years later permission was even given to priests to attend cremations and hold services in cremation chapels. For all its popularity, the clergy themselves were reluctant to be cremated and my liberally-minded great-uncle, Mgr William Denning, was only the third Catholic priest to opt for it in 1980. Cremation remains forbidden to the Greek, Russian and Jewish Orthodox, Muslim, Parsee and Zoroastrian communities.

There is no easy way of finding out where an ancestor’s cremation took place. The desire to be cremated might be specified in a will, although from 1965 it has been legal for people to cremate dead relatives regardless of whether the deceased person had wanted to be or not. The best you can do is to find out where they died from their death certificate, and then locate the nearest crematorium by asking the Cremation Society of Great Britain. You can then ring or write to the crematorium, whose staff will usually be helpful and check their records for you. You can expect to learn the name, date and place of death and normal residence of the deceased, as well as the name and address of the person who booked the cremation and the names of the two doctors- a prudent measure introduced by Thompson himself – who certified that the body really was dead.

The ashes may be scattered in the crematorium’s garden of remembrance, or elsewhere as specified in a will or decided by the relatives. For a mere £9,000, some have even opted to have a tiny phial of their ashes blasted off to the moon, or even further, on the Voyager missions, far into the depths of space, beyond even Shelley’s imagination.

(C) Copyright Anthony Adolph 2012