Scott Crowley and Anthony Adolph

This is the story of our journey to Scotland to find out about Scott’s maternal ancestors, the MacLeods of Badnaban.

We set out for Scotland on a bright 21 September 2006, flying to Glasgow and driving north to Fort Augustus on the southern shore of Loch Ness and continuing through ever more dramatic scenery to Skye the following day.

Dunvegan Castle

On 23 September, following the footsteps of Dr Johnson and James Boswell 213 years earlier, we made the first of our special visits to MacLeod sites, Dunvegan Castle. The seat of The MacLeod of MacLeod, chief of the clan, Johnson described the castle emphatically as the clan’s ‘centre of gravity’.

Parts of the castle, including the well and the curtain wall around the Gun Court, are said to have been built by Leod (c. 1200-1283), the eponymous founder of the clan. In the castle, we saw the faded, almost disintegrated remains of the Fairy Flag. There are many stories of how the flag, am bratach sith, which is about 1600-1300 years old, came into the MacLeods’ possession: some say it was given them by fairies: some versions include the information that it was used by King Harald Hardrada, a cousin of Leod’s, as his standard at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066.

The Dunvegan Cup was given by the O’Neils of Ulster to Rory Mor, Chief of the Clan, in about 1595, to thank him for helping them in their war against the English invaders – the original wooden vessel that is encased in silver dates back to about 900 AD. Next to it was Rory Mor’s horn, a reminder of the days when the Macleod chiefs were very much the warrior leaders of their clan. Leod acquired Dunvegan by his marriage to the heiress of the Macrailts, the Viking seneschals of Skye, who lived at Dunvegan – there is in fact evidence of a fort on the site dating back to the Dark Ages.

In 1263, King Alexander of Scotland defeated the Vikings at the Battle of Largs and gained control of the Hebrides. Although Leod was a Viking, his descendants retained control of their lands but henceforth ruled not as Viking lords, but as Gaelic chiefs, using the name MacLeod – ‘son of Leod’.

A small boat goes out regularly from Dunvegan to the nearby isles, in the shadow of the flat-topped mountains called MacLeod’s Tables, to show visitors the seals. Like Leod himself, therefore, we embarked by boat and ploughed through the crested waves to the little rocks, and there saw the seals, who in turn watched us with their baleful eyes, and I was reminded of the ancient Gaelic tradition that seals have the souls of the dead. If so, the souls that gazed out at us from the bodies of those seals may have been those of Leod and his family, Scott’s distant forebears.

Meeting Mrs McBain

On 24th we drove north from Skye to Ullapool and then plunged up the ‘mad wee road of Sutherland’ to Inverkirkaig. Scott knew that his grandmother Alexandrina MacLeod, known as Alice, had gone to Glasgow as a domestic servant, from a croft in Badnaban, where his great grandfather Alexander Alistair MacLeod, known as ‘Ally Alistair’, had farmed. Our expectations soared as we drove along the beautiful coastal road, but clouds had gathered and the sun went in, and when we reached it Badnaban, whose Gaelic place name means ‘the place of women’, looked a dismal place.

We found No. 22, supposedly the family croft, but found a fairly modern-looking bungalow, near an unnumbered old croft, which had clearly been renovated very recently. Nobody was in: looking at the rainswept croft, we weren’t surprised Alice and her sister Barbara both left to enter domestic service in Glasgow. An indoor servant’s life was a hard one, for sure, but it didn’t involve scrabbling about in boggy mud uprooting turnips and gutting net-fulls of fish.

We left, too, rather downhearted, and found our Bed and Breakfast, ‘Davar’, at Baddidarrach on the other side of Lochinver harbour. The proprietor, Mrs McBain, was very friendly, so we told he why were there. ‘I knew the MacLeods of Badnaban!’ she exclaimed. She knew Scott’s great uncle Jimmy as ‘Jimmy Alistair’ and said ‘I knew Jimmy and Greta very well – in fact I was at their funerals’. Jimmy was Alice’s brother, who took over the croft when Ally Alistair died.

‘And of course’, Mrs McBain said, ‘I remember poor Sandy’. Sandy was Jimmy and Greta’s adopted son, who was killed in a car accident, aged only 24. ‘Och, everybody loved Sandy’, she added, sadly, and told us where on the road just outside Lochinver he had driven his car straight into a cliff face. ‘He hardly ever drank, but he did that day…’, she told us: she had been to his funeral too, and his burial up the coast at Stoer.

Badnaban

Mrs McBain told us a bit about life at Badnaban. They had cows for milk and lots of sheep. Everybody had their own boat and caught prawns, salmon and lobsters, using the creels that are still piled up on the tiny harbour wall there now. They also caught venison, something that puzzled us until we later asked Scott’s father about it and he confirmed that this was, indeed, poaching – ‘but where was the deer inspector?’. Off they went onto the moor with a gun, and back they came with a red deer slung over the shoulder, or if it was too heavy two halves in two journeys, made circumspectly by night.

Mrs McBain also confirmed that the old family croft was the renovated one next to what is now numbered 22, and that the current owner, Alison Robertson, worked in the local bank. The followingmorning, then, we presented ourselves at the counter of the Royal Bank of Scotland and introduced ourselves. Somewhat bemused, Alison said we could go and ‘poke about’.

Badnaban on a sunny September morning looked very different to the day before, the red rowan berries ruby red against the brave blue sky and the burn chattering down to the shining sea. Maybe Alice hadn’t been so keen to leave after all – did she jump, or was she pushed by the family’s need for ready cash? They were virtually self-sufficient, Mrs McBain had said, but they still needed money to buy paraffin, and other necessities – and to pay the rent!

The croft has been lovingly modernised, the ‘harling’ (roughcast) that used to coat the stone walls has been stripped away to reveal the original stonework and in the garden where the MacLeods once grew vegetables and kept their chickens there is now a manicured lawn and modern decking. The old outhouse is still there, now serving as a rather ramshackled garage, and on the croft’s old land now stands a holiday chalet and the newer, whitewashed house that we had encountered the day before, now numbered 22.

Cnocaneach

Just down the coast was Inverkirkaig (pictured below), where in 1597 a bloody battle took place in which Ian Beag MacLeod of Handa, a kinsman of the MacLeods of Assynt, captured and killed John Missison, hereditary breve of Lewis. It is now the home of the only local bookshop, where we hoped to pick up some MacLeod literature. There was disappointingly little, but the owner (whose wife was a MacLeod) showed us two books by the local historian, Malcolm Bangor-Jones, Historic Assynt and The Assynt Clearances. We spotted a third, Population Lists of Assynt 1638-1811. ‘What about this?’, we asked. ‘That’s just for hard-core genealogists’ he said. ‘We’ll have it!’ we replied.

The Assynt Clearances is a study of the forced removal of the population of Assynt, which was part of the great Sutherland Estate in order to make the most fertile land available for commercial sheep farming. The process, which throughout Scotland spanned the period between the 1760s and 1860s, lasted in Assynt between 1812 and 1821, when the factors, William Young and Patrick Sellar, created five great sheep farms by evicting over 160 families from their relatively fertile inland farms to the rough, boggy land around the coast, where they were invited to eke a new living out of smallholdings, kelp-making and fishing. Over coffee in the bookshops’ tiny café, we leafed through looking for MacLeods mentioned in context of Badnaban. There was only one entry:

Cnocaneach Cnocaneach and Badnaban were held by George Ross from Easter Ross who went on to work for the Custom House in Ullapool. He had removed people from Cnocaneach prior to 1812. The MacLeods, who were removed when the lands became part of the Culag sheepfarm in 1812, accepted holdings in Baddidarrach but then changed their minds.

| Cleared | Head of Household | Destination |

| 1812 | Alexander MacLeod | Langwell sheepfarm, Coigach |

| 1812 | Angus MacLeod (son of the above) | Badnaban |

| 1812 | Roderick Ross | Bad a’ Ghrianan |

The day before, we’d had a walk around Baddidarrach (pictured below), up over the hill overlooking the harbour towards Badnaban, and thence to the great sugarloaf bulge of Suilven, an ancient volcanic core of rock left isolated by the glaciers in the Ice Age. Baddidarrach was a pretty bleak place, the ground either bare rock or suppurating bog, and no place to make a home. Badnaban was presumably a slightly more attractive option, because it was on the same side as the estuary as Lochinver, which had been founded as a fishing port in 1775.

We were now fascinated that the MacLeods of Badnaban had lived elsewhere before 1812. We scoured the 1:25,000 Ordnance Survey map of the area that we’d bought presciently beforehand, and Scott emitted a cry of triumph when he found ‘Cnocnaneach’, just under two miles due east of Badnaban, an uninhabited spot but clearly marked with a track and what looked very much like a building.

We drove as far as we could, up a road from Lochinver and then walked, past the shores of the beautiful Loch Druim Suardalain (‘Drumswordlin’), under the distant slopes of Suilven, and up through a wooded ravine, under the slopes of Cnoc nan Each (which I believe means ‘hill of the mound’). The stone walls of the sheep farm came together where the house was – a ruined croft, and then, just round a bend in the track, Scott emitted a second cry of triumph at the site of a ruined house, not deliberately pulled down like the other, but still very much derelict. It had been rebuilt, according to a date-stone in the wall, in 1870, but we knew that many newer homes were built on the foundations of ruined ones. No other ruined buildings could be seen, but the outline of several small ruined paddocks, were obvious. The MacLeods and the Rosses had been thrown out of Cnocaneach in 1812 – and here were two ruined houses.

It would have been a pretty tough place to live, but nowhere near as much as Badnaban. Instead of a smallholding squashed between the road and the burn, the farm at Cnocaneach was set in a sheltered valley, proudly independent of anywhere or anyone else, with fertile pastures for cattle, plenty of land for growing vegetables and hay, a wood nearby for fuel and a burn running into the loch, for drinking water, washing and fishing trout, especially the notorious local ferox trout, that prey on others of their own species.

The clearances destroyed many old settlements: inland Assynt is littered with the ruins of houses, kale-yards, and areas of cultivation rigs and lazy beds which were ridges made by laying seaweed, dung and used thatch over the bog, for growing oats and potatoes.

Some clearances were enforced by violence: in extreme cases, some tenants actually died when their farms were burned down around them. The area certainly saw violent protests, and we read that the residents of Inchnadamph rioted in 1813 when a minister who favoured clearances was appointed. Most clearances, however, took place relatively peacefully, the landlord waiting until the lease ran out and simply refusing to issue a new one.

The MacLeods probably went quietly, but as we walked back down the track to the loch we felt an immense sadness knowing we were walking in the footsteps of the departing MacLeods, who lead their animals away, all their worldly goods tied to a cart, that grim day in 1812. They were being separated, father Alexander to the Langwell Sheep Farm, and son Angus to Badnaban, where he knew his ability to provide for his family would be seriously impaired.

A surprise encounter

We returned to Lochinver feeling elated that we had found Cnocaneach, and saddened with the knowledge of what had happened to the MacLeods, who had gone from comfortable tenant farmers at Cnocaneach to crofters eking out their lives in Badnaban.

Whilst climbing over a fence to get nearer the ruins, I’d torn my trousers, so we went into the local post office to buy a needle and thread. The postmistress was as friendly as everyone there, and when we said we were investigating the MacLeods she said ‘Alison McLean at the Council Offices is the daughter of a MacLeod from Badnaban!’. We thought ‘why not?’ and went round to the office, which is behind the Culag Hotel on the harbour front, and asked for Alison. She was out, they said, ‘but her daughter works here. Would you like to see her?’.

Thus we met Elaine McLean, who was completely bemused by our presence there, and simply didn’t know whether she was related to Scott. She therefore rang her grandmother, Mrs Nan MacLeod, and let Scott talk to her. She certainly remembered Jimmy, Greta and the tragedy of Sandy, and invited us to visit her the next day.

Finding graves

We knew from Mrs McBain that Jimmy, Greta and Sandy were buried at Stoer, but Nan told Scott on the telephone that Ally Alistair was in fact interred in Lochinver churchyard, which we’d already been past several times coming and going from Mrs McBain’s B&B. Back we went, then, and under a bright September sky poked about through the gravestones.

We saw MacLeod after MacLeod, but eventually Scott emitted his third exclamation of triumph, when he found a stone saying the following:

Erected by the family

In loving memory of

our father

Alexander MacLeod

Badnaban

died 14th Aug. 1940

Also our mother

Mary White

died 23rd Nov. 1940

Also our sister

Annie MacLeod

died 22nd July 1971

We learned later from Nan MacLeod that it was probably Jimmie who had put this up.

We left Lochinver, driving gingerly past the spot where Sandy had his fatal crash, and on to Stoer. It is several miles away up the coast, in a gorgeous bay of vivid emerald grass, nestling amidst enormous cliffs. There are three graveyards, starting with the original one at the top of the hill, then the ‘old’ one and below that the ‘new’ one. We told a very old lady who was walking down the road with her mother what we were doing, and they said ‘the Lochinver people are buried in the old cemetery, on the left [ie, the east] side’.

Sure enough, there was Jimmy and Greta’s little grave, marked by a marble stone in the shape of a book, and next to it a larger black marble slab commemorating poor Sandy: he died in February 1976, and poor Jimmie died in July 1978. Greta outlived them both, dying in 1986, after which the croft in Badnaban was sold.

Ardvreck Castle

We spent that night further north at Kylesku, which looks up into northern Sutherland, the extreme north-westerly part of Scotland. The next morning we went south, keen now to see Loch Assynt and Ardvreck Castle. Leod’s eldest son Tormod ruled Syke, Harris and Glenelg, where his descednants, the Siol Tormod, remain. One of Tormod’s grandsons Torquil, married the heiress of the MacNichols of Lewis, ensuring his own lordship there by drowning all his in-laws. He is the ancestor of the Siol Torquil. Torquil received a royal grant of Assynt in 1343, promising David II of Scotland the service of a 20-oared Hebridean galley, an essential tool in maintaining royal authority in the Western Isles. Torquil left his lands to his son Rory, on whose death the lands were split, Lewis going to the oldest, also called Torquil, and Assynt going to the second son, Tormod. It is from Tormod that the MacLeods of Assynt are descended.

The MacLeods of Assynt multiplied into a formidable clan, based in their castle of Ardvreck, pictured above. They were a querulous lot, and the dungeon at Ardvreck was often full of other MacLeods, or their near neighbours.

The family was a very romantic one – and it was also extraordinarily violent. In the generation of the sons of Angus Mor MacLeod in the sixteenth century, for example, one of the sons was murdered by his brother, who was in turn killed in revenge by one of his father’s illegitimate offspring. The next brother was Neil the Tutor, who had a dispute with the final sibling, Houstian. Neil invited Houstian and Houstian’s son Dougal to Ardvreck. Having got them drunk, Neil drew his dirk and stabbed them both through the heart, despatching them in cold blood in their own family castle, in flagrant violation of the laws of hospitality and the bonds of kinship. Neil was executed for this dastardly act in Edinburgh in 1581. His and Houstian’s remaining sons called a temporary truce to oust their semi-crippled nephew, Angus, who had come of age, but soon the thugs fell out amongst themselves over fishing rights, and soon the bodies were piling up again in an internecine civil war that left Assynt awash with blood.

The prize for the most utter venality, however, must go to the unnamed chief of the MacLeods of Assynt whose story appears in The Sutherland Book:

One night an elegantly dressed gentleman called at Ardvreck and was entertained, meagre though the fare was. During the meal he disclosed his identity as the Devil and proposed that for the soul of MacLeod he was prepared to reverse the fortunes of the family and make the crumbling castle of Ardvreck finer than Dunvegan itself.

MacLeod was afraid and declined, but the Devil was not to be outdone. Waiting at table was the beautiful young daughter of the house who was impressed by the stranger and the interest he was taking in her. The association grew as the days passed and, in the end, the Devil proposed a new plan to MacLeod. For the hand of the daughter, he would restore the MacLeod fortunes just as if it was the soul of MacLeod he had won.

MacLeod, in his greed, consented and the unsuspecting daughter was given in marriage to the stranger. The wedding celebrations were the grandest ever seen in the west but just as the couple were leaving the castle after the wedding to sail to the shore a violent thunderstorm broke out. The couple sailed into the darkness and were never seen again. MacLeod received nothing of the fortune the Devil promised him and when he died his line expired. Today the castle stands in ruins on its island in Loch Assynt. On nights when thunder rolls in the surrounding hills and lightning plays on the dark loch, the screams of a woman can be heard and a figure in white is seen weeping on the stony beach by the ruined castle.

Very few families can claim the Devil as an in-law, but the MacLeods of Assynt can!

In 1650, Neil MacLeod (1628-c. 1702), 10th baron of Assynt, blotted his historical copybook by capturing the glamorous Royalist commander the Marquis of Montrose sending him to his death on the executioner’s block in Edinburgh. As the local sheriff depute, Neil was only doing his duty, but the act appalled many, and in Aytoun’s The Execution of Montrose we read that:

A traitor sold him to his foes;

O deed of deatless shame!

I charge thee, boy, if e’er thou meet

With one of Assynt’s name –

Be it upon the mountain’s side,

Or yet within the glen,

Stand he in martial gear alone,

Or backed by armed men –

Face him, as thou wouldst face the man

Who wronged thy sire’s renown;

Remember of what blood thou are,

And strike the caitiff down!

… an injunction happily not practised on Scott, at any point in our journey, despite his telling everyone his grandmother had been a MacLeod! After Charles II was restored in 1660, however, Neil MacLeod became politically isolated. Particular enmity had always existed between the MacLeods and the MacKenzies of Ross-shire. Now they started buying up Neil’s debts and, in December 1671, they claimed Assynt as their own. The sheriff came to order the MacLeods to leave, but they refused to obey the royal official’s orders and tried to brain him with a rock.

In June 1672 the Mackenzies obtained ‘letters of fire and sword’– authority to use force – and invaded Ardvreck. Under Neils’s son-in-law John MacLeod, the garrison of 18 held out for two weeks until faced with a formidable siege engine made by Sir George MacKenzie of Tarbat. Realising the game was up, they surrendered and were expelled from their ancient seat. The MacKenzies built an elegant mansion, Calder House, on the shores of the loch, the ruins of which are pictured below. The idea was to be able to look out on their captured castle and reflect on the humiliation of their ancient foes, but their act of vanity cost so much that in 1739 they went bankrupt and their estates were bought by the Earls of Sutherland in 1757.

One branch of the MacLeods of Lewis retained land-owning status, on Raasay, off the eastern coast of Skye, which we could see from our B&B window whilst staying at Portree. They held on until 1846, and a descendant of theirs has been recognised by Lord Lyon as The MacLeod of Lewis. It was not hard, however, to see how the rest of this once-powerful clan, whose wealth was based mainly in cattle, could be reduced by time and fate to the status of tenant farmers, only to suffer further degradation in the Highland Clearances.

As we approached Loch Assynt, therefore, and saw Ardvreck castle for the first time, we knew that this could very easily be the home of the ancestors of Alice MacLeod, who went to Glasgow to become a servant.

The ruins of the little castle, recently shored-up by the Historic Assynt Trust, are indescribably romantic, standing in their proud dishevelment on the little windswept island, connected to shore by a single boggy track. The MacKenzies, whose ruined house can be seen just down the strand, let it deteriorate, and in 1795, in an incident worthy of Byron’s Romantic imagination, it was struck by lightning. The stones we can see now belong to two phases of building, one in about 1500 and the second about 1590. We know little of life there, but we know they had a watchman (a ‘cocker’) and doorkeeper, and that in February 1649 the aged Donald MacLeod of Assynt made an oath ‘in the Castle hall of Ardbrak… sitting in his schear [chair] and taking Tobacco thairin be Ten hours before noone’.

MacLeod’s Tears

We drove a mile or so south along Loch Assynt to Inchnadamph, where we found two local history booklets by Mrs Margaret Campbell, one about the castle and the other about the MacLeod Vault.

It turned out to be right there, in the churchyard at Inchnadamph, a great, solid stone block partly overgown by ash trees. The original church at Inchnadamph is said to have been built by Angus MacLeod of Assynt about 1440, on his return from a pilgrimage to Rome, and the vault is thought to be part of the original building, the new one being a few yards away.

The way in to the vault had been blocked, as the interior, full of the bones of the MacLeods of Assynt, all jumbled together, is unsafe. Just as well, too, for a permanent and inexplicable drip of water falls from the vault’s door and, it is said, if it falls on you, you’ll die soon afterwards. The drip is called ‘MacLeod’s Tears’.

Meeting Nan MacLeod

The next stop was Mrs Nan MacLeod, back in Lochinver. Over coffee in her flat, this wonderful 86 year old lady told us her memories of life in Badnaban, where she lived the first 84 years of her life. She was born in the croft nearest the shore.

The great thing was that she remembered Scott’s great grandparents Ally Alistair MacLeod and Mary Ann White: her memory was extraordinary. She remember that Ally Alistair died in 1940, and knew about his siblings, and even remembered Scott’s mother and aunt Helen coming there as children, almost 60 years ago. She knew that Scott’s MacLeods were related to her, but was quite vague as to how – she seemed most closely related to Greta, but thought that the MacLeods themselves were cousins – ‘some people you knew you were related to, and some you weren’t’. She very kindly gave us some old photographs, including one of Jimmy and Greta, and another of Badnaban as it used to be, in snow.

Amongst her memories were several of Alice herself. She had black wavy hair, blue eyes and pink cheeks. Later, we were sent some old family pictures by Scott’s cousin Kay, including one of Alice – looking exactly as Nan had described her from memory. Nan told us that Alice worked as a servant, first for a local doctor and then in Glasgow. According to Nan, all the local girls ‘wanted to get away’: they earned ‘a pittance’ but would still send some money back home. She and Babs would return for two weeks’ holidays each summer, before they married.

Holidays were important, as the local minister highlighted, amongst other things, in the 1795 Statistical Account:

They are patient of hunger, cold and fatigue, by sea and land, as emergencies may require. In general, they are serious and devout, and do not approve, but highly dislike the contrary character whenever seen… their manners are simple and chaste, few instances, comparatively speaking, have occurred here to the contrary, for these 25 years past, and when they have happened they were candidly acknowledged. Of customs, it says that ‘in time of holidays, relations and neighbouring families mutually visit, and cheerful and facetous…’

Alice’s mother was Mary Ann White, shown below in another of cousin Kay’s pictures, at Badnaban with one of her grandchildren, Murdo. The other picture shows Murdo with his parents Roddy and Dolly. To return to Nan MacLeod:

There were two Marys who came to Badnaban from the east coast, Mary Morrison who married Donald Wilson in Inverkirkaig, and Mary Ann White. Mary Ann made lovely scones, pancakes, gingerbread and shortcake on her fire (‘you’d be cooking on the fire when a lump of soot would fall down’) – they later graduated to a primus stove and Raeburn, from which Nan used to pinch scones. She had fruit trees in the garden and was’ always making jam’ that she sometimes gave Nan.

Mr McKie delivered groceries on the dot of 10.20 each Tuesday ‘you could set your watch by him’. You got change out of 10 shillings for 1lb butter; 1lb cheese; tea, sugar, a loaf, tobacco and a tin of corned beef.

Alice’s father Ally Alistair. He was ‘a bit grumpfy’ unlike his son Jimmy.

He kept sheep and fished. He sold his fish at the Haddiebank down the coast near Inverkirkaig, They would fish in all weathers, and if a storm caught them they might have to put in further down the coast, in which case a child would be sent running down to see if they were safe. Lobster fishing was done in the winter. The lobsters were packed in straw and sent to Billingsgate on Mondays and the money came back on Thursdays. At Christmas the Billingsgate fishmongers sent them colanders as presents.

The fast-flowing burn next to the croft provided all the water they needed for drinking and washing. Ally Alistair had three cows and a horse called Lilly, used for ploughing, and also kept the local bull for a while. Nan was terrified of it and used to walk a long way around to avoid going near it. There was a huge sack of corn at his croft. They kept sheep on the hills in summer and at the croft in winter. They took wool to Dingwall, a trip lasting two days, and used the money to buy sacks of oatmeal, which were very dear at £3 a sack. They sold lambs at the market in August and sheep in October, but a top lamb only sold for 6 shillings. They grew vegetables – Nan used to steal some of their turnips and commented on ‘the lovely taste of a fresh turnip’. Now the land used for vegetables is full of rushes.

Jimmie ‘would do anything for anyone’ (Nan). He was in the Navy. He was away a few years, but returned a few years before his father died.

An earlier Jimmie was bitten by an adder and died.

An earlier Archie ‘hit the bottle as well’.

Roddy, brother of of Ally Alistair. Nan remembered him giving sweets to all the local children when he was still living in Badnaban. He became a gilly on an estate owned by a surgeon in Inverness. Initially, he and Jimmie used to see each other, but ‘it faded away’ and he never came back. . He had an accident whereby he was struck on the head by a hook used for hanging haunches of venison and was then found to have a tumour in his head. ‘We didn’t realise what a tragedy it was at the time’, Nan said, for the tumour eventually killed him.

Elphin

Thanking Nan profusely, we continued on our journey. Scott’s great aunt Babs, who had also left for Glasgow, had told her daughter ‘wee Babs’ that the MacLeods were originally from Elphin. Both Mrs McBain and now Nan MacLeod had confirmed this (though it’s not clear whether they knew it for sure, or we were simply hearing the same story from different people). Elphin lies further south, between Badnaban and Ullapool, so south we went.

Elphin and neighbouring Knockan were inhabited by two tacksmen and 24 tenants until 1812, when the area was the only inland area of Assynt to be chosen for the victims of clearances. The area was divided into 58 crofts but in the 1840s they suffered terribly in the potato famine and the Duke of Sutherland decided to clear them again. They were offered free passage to Canada or resettlement on the coast. They resisted fiercely, burning their eviction notices and fighting the sheriff’s men and they were subsequently left in peace, though most did in fact leave of their own accord. Now it’s virtually deserted, with only a few Highland cattle grazing in its lonely fields.

Langwell Sheep Farm

We continued south to stay in Ullapool, but as we drove along Scott noticed a sign to a now quite familiar place ‘Langwell Farm’, Coigach. This, we remembered, was the destination of Alexander MacLeod, father of Angus who settled in Badnaban, when he was cleared from his home at Cnocaneach. We drove down a long road through a broad glacial valley, with many sheep on the fertile hillsides around us, but were disconcerted by a notice at the bottom reading:

STALKING WITH HIGH VELOCITY RIFLES IN PROGRESS. YOU ARE STRONGLY ADVISED NOT TO PROCEED FURTHER.

We did not, but when we reached the B&B (‘the Sheiling’) in Ullapool we asked the owner, Mr MacKenzie, if he knew who owned the farm. Yes, we were rather trepidatious of asking help of a MacKenzie, but he was very kind and told us that he was one of the stalkers there, and gave us the number of the owners, Mr and Mrs Fenwick.

The Fenwicks kindly invited us to call in the next morning, and assured us we would not be shot. ‘This was all MacLeod county’, they told us, but in fact the marriage of Margaret Macleod of Lewis and Rory MacKenzie, second son of the MacKenzies of Kintail in 1605, seems to have brought Coigach into MacKenzie hands. Bangor-Jones’s history of Assynt actually says that in 1725 Angus, son of John Maceanreoch alias MacLeod, a cousin of Neil MacLeod of Assynt, reduced to poverty, became a servant to the MacKenzies there.

It seems, then, that by going there to find work himself, old Alexander was to some extent following the footsteps trod by Angus MacLeod in 1725.

The farm was a fine place. It had been established there in about 1809, in buildings rebuilt after the older ones had been burned down by English sailors who came up from Ullapool in the wake of the ’45. Although Alexander’s life had taken a downward turn, it can’t have been a bad place for him to have worked. The MacKenzies were the Earls of Cromarty, with the subsidiary title of Lord MacLeod, and certainly didn’t live at Langwell, so it is possible, as the house was the grieve’s house, that a MacLeod was the grieve there, as a tenant of the MacKenzies.

Inchnadamph

Our final appointment was with Mrs Helen Morrison at Inchnadamph, who had agreed to show us the old church, next to the graveyard where the MacLeod Vault stands.

It turned out that the Historic Assynt trust has been working for the last few years to preserve the vault and castle, and also to turn the old church into a Heritage Centre. Its grand opening had actually been the week before, so to our surprise we were shown a grand pedigree of the MacLeod chiefs at Assynt, and copies of the local school records and censuses. The former showed us that old Ally Alistair and his siblings had a good education at Lochinver School.

That was as much as we learned on our trip to the Highlands, although we did enjoy looking at earlier archaeological remains. Although Leod was a Viking, the MacLeods married into many local families, who were a mixture of Scots (originally invaders from northern Ireland) and Picts.

Writing in 140AD, the geographer Ptolemy of Alexandria describes the Picts, the aboriginal inhabitants of Scotland, and names their tribes. Those of the Assynt area were the Caeroni or Caronacae, the ‘sheep people’. We saw the chambered cairn on the dry land next to Ardvreck Castle, where ancestors of the later population were buried about 4,000 years ago. Beating that for antiquity, we can go back yet further with the Bone Caves, a couple of miles down the road from Inchnadamph, towards Elphin.

We climbed up to these four magnificent caves, where some of Scott’s ancestors must have lived over thousands of years, up to as recently as 2,700 BC – four of them were found buried here, along with the bones of the animals they hunted, especially red deer. Earlier bones of reindeer and bears have been found there, some dating back 45,000 years. It was an ancient site, in a much more ancient landscape, for the Lewisian Gneiss of Assynt is amongst the oldest to be seen on the surface in any part of the globe, being part of the original earth’s crust, formed of frenzied lava spouts, some 2,500 million years ago.

For our last night, we stayed at the Inchnadaph Hotel, and after dinner we walked down to the graveyard to see the MacLeod Vault by starlight. There are plenty of ghost stories associated with the family, including a grey woman who haunts the shore at Ardvreck, having married a wealthy stranger who came to dinner in the days of the MacLeod’s disgrace after their ‘betrayal’ of Montrose, and transpired to be the Devil himself.

Great Aunt Babs

The following morning we drove south to Glasgow to see Scott’s parents, and on the next day we made the last stage of our journey, with Scott’s father (his mother had a cold and could not go), to a nursing home in Inchinnan, Renfrewshire, to visit Scott’s great aunt Babs. At 96, Babs is the last surviving child of Ally Alistair, and we were obviously intrigued to see what she could tell us. She is very elderly now, and quite confused – she thought I was her nephew Rory – but when Scott showed her the pictures of Badnaban and her old friend and relation Nan MacLeod, her memories of childhood were both clear and witty.

Babs stated that her father’s father had moved to Badnaban – he would have been 2 in 1812, and therefore born at Cnocaneach. She also told us:

Ally Alistair. Had horses including one called Ness. His boat was called ‘The Nain’, ands she remembered the ‘lovely big lobsters’ that were sent away to Billingsgate. During the First World War he was in the Navy. He died aged 79 (she said 80), commenting ‘up there they died young’ – apparently, 80 was young and 90 old.

Mary Ann White was from Lossiemouth. She lost touch with her family there because there were no telephones.

Alice and Walter Hooks, her husband, would come back to visit occasionally, by car.

There was a family bible, but Greta buried it.

Lobster fishing still goes on in Badnaban, to this day, as we saw when we were there. Incidentally, another local MacLeod, Neil, of Polbain in Coigach (1855-1938), was a noted Gaelic poet and one of his surviving works, is Iasgach A’Ghioaich, ‘Lobster Fishing’, which paints a vivid picture of the grim reality of lobster fishing:

Sailing along with Barney to the foot of Rhu Mor,

Black and gloomy and grey grew the sky with clouds;

A north wind sought to blow, a snarl on every point,

The Bows were awful, no fun to be near them.

……

When we reached the anchorage and furled away her sail,

We were wet and hungry no spark of fire aboard;

It’s the lobster fishing that took my courage and strength away,

I’d sooner be a mason with a trowel in my hand

Life would have been no less easy for the female MacLeods, waiting at home anxiously for the men to return.

Thus, to our great question of why she and Alice had left Badnaban, Babs was perfectly clear. ‘It was a dump!’ she exclaimed ‘cows all over the place knocking down the fences’. Scott’s mother knows that Babs went down to Glasgow five years after her sister Alice. Alice worked at Kilmalcolm, earning 10 bob a week, and graduated to being the silver service servant – a far drier, warmer and from her point of view socially elevated job than grubbing about in a north-western croft.

A moment of reflection

Alice’s was the first generation in Scott’s line to leave an area that Leod had settled in some 800 years earlier. She was glad to go, yet for us the experience of going there – or in Scott’s case ‘going back’, was extraordinary, and moving.

From my point of view, it was a fascinating exercise in genealogy in the field. From Scott’s, much more importantly, it was a journey back into his own origins.

Reflecting over a glass of ‘MacLeod’s Tears Whisky’, Scott reflected that whilst the journey had confirmed some of the things he had known about his family, it had also revealed many that he had never expected or even suspected.

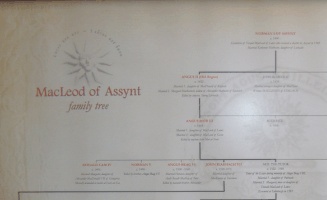

Appendix: The ancestry of the MacLeods of Badnaban

We returned to London with a mass of information on MacLeods that we now had to sort out.

Although Scottish records are very good back the 1850s, they deteriorate rather rapidly before then and the earliest entries in the Assynt parochial register are only from 1798. However, there are earlier population lists (collected and published by Mark Bangor-Jones) that enable some tentative reconstructions of family trees. To confuse matters further in Scott’s case, Ally Alistair’s immediate family tree included several intermarriages of MacLeods.

The conclusions I reached on our return from Assynt in September 2006 have since been revised and changed several times in light of new evidence, the most recent being from a distant relative of Scott’s, Roddy MacLeod, who knew of oral traditions collected by an earlier relative, Kenneth MacLeod, in the Inverkirkaig area in the 1960s. It seems now that Ally Alistair’s father’s father Angus MacLeod may well have been, as Babs and Nan thought, from Elphin. Angus’s wife Margaret was also a MacLeod (her brother Roderick was Roddy’s ancestor). Her branch had been cleared from Concaneach shortly before 1812: the Alexander and his son Angus who we had found being cleared from there seem to have been cousins of hers. It seemed a shame, initially, to have taken so much interest in this last pair when it turns out they were not direct ancestors of Scott’s, but they were kith and kin, none-the-less, and finding out about their experiences had taught us a lot about the reality of the Clearances.

Using the population lists, I have pieced together a tentative line of descent for Margaret (and thus for her descendants Ally Alistair and Scott) going back to a much earlier Roderick Macleod, a younger son of Donald Ban MacLeod (d. 1647), Chief of Assynt. This is described in detail in my book Tracing Your Scottish Family History (Collins, 2008).

Bibliography

An Trubhal Na Mo Dhòrn, ‘A Trowel in my hand’, songs and poems by Neil MacLeod, the Polbain Bard, collected and translated by Roderick F. MacLeod, published by Roderick F. MacLeod, 2005.

Assynt Old Parish Church and the Macleod Burial Vault at Inchnadamph, Maggie Campbell, Historic Assynt, 2002

Land of Rocks and Lochs, a guide to Assynt and Lochinver, Nick Kerr (ed), Galatea (UK) Ltd, 1993

Ardvreck Castle and Calda House, Maggie Campbell, Historic Assynt, 2002

Historic Assynt, Malcolm Bangor-Jones, The Assynt Press, 2000.

The Assynt Clearances, Malcolm Bangor-Jones, The Assynt Press, 2001.

Population Lists of Assynt, 1638-1811, Malcolm Bangor-Jones (ed), 1997.

Dunvegan Castle, John MacLeod of MacLeod, MacLeod Estate Office, 2005.