PERRY NURSEY

Perry Nursey 1771-1840

NOTICE: To the Nobility, Gentry and all Persons of Discernment and Taste and Lovers of the Fine Arts, Mr Anthony Adolph of Mole Cottage, Beckenham in the County of Kent, Genealogist, Writer, Broadcaster and Artist, begs Leave to Announce the Publication of his New Catalogues of the Artistic Works of his late esteemed Ancestor Perry Nursey Esq. (1771-1840), late of The Grove, Little Bealings in the County of Suffolk, associate of John Constable’s, and of his sons, Rev. Perry Nursey (1799-1867), Rector of Crostwick, in the County of Norfolk, and Claude Lorraine Richard Wilson Nursey (1816-1873), late Head Master of the Government Schools of Art in Belfast, Leeds and Norwich, founder of the Braford School of Art and inspiration for the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Fully Illustrated in the new Colour Photography and each Work Numbered according to Mr Adolph’s New System of Classification. Copies of these Unique, Beautiful and Rare Publications may be had at the Modest Price of Fifteen Pounds apiece by application to the Author or at Mr John Day’s East Anglian Traditional Art Centre in Wickham Market in the County of Suffolk.

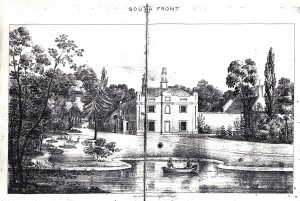

Perry Nursey (1771-1840) of The Grove, Little Bealings, was a landscape painter, who loved the Suffolk landscape, and pioneered the practise of painting outdoors, so as to capture the freshness of nature in a way that was impossible in the more practical environment of a studio. Nursey was also an architect and landscape gardener who left his mark on some of Suffolk’s gardens and mansions, which he developed in his distinctive, Picturesque style.

Perry Nursey is my great great great great grandfather, and over the years I have become extremely fond of him and his work, which has led me down many highways and byways in Suffolk, over and again.

As a genealogist, I have also enjoyed exploring Perry Nursey’s ancestry; his mother was a Fairfax and shares the same Fairfax ancestry as H.R.H. The Duchess of Cambridge, a line which goes back, ultimately, to the Plantagenets. Perry Nursey’s home, The Grove in Little Bealings, was inherited by his wife Anne Simpson, whose own ancestors, the Simpsons of Wantisden, the Benningtons of Butley and the Barthrops of Hollesley, are the subject of ongoing research.

The following is a short essay which I wrote about Perry Nursey in about 1998, and which I updated in 2019.

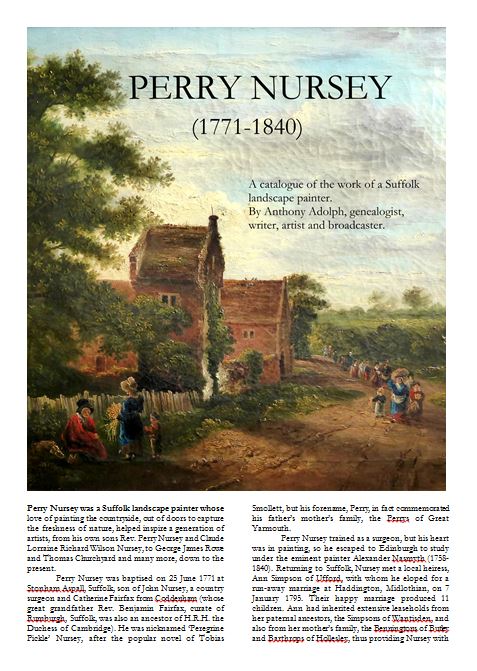

PN6. Perry Nursey, ‘Seckford Hall Lodge, on the road between Little Bealings and Woodbridge, Suffolk, with workers returning from the fields’,

PERRY NURSEY: PAINTER OF THE PICTURESQUE

In the late eighteenth century, when Perry Nursey (1771-1840) was an eager young painter, landscape painting could be as controversial as preserved sheep and unmade-up beds are in today’s art-market. You could either be as grand as Gainsborough or Ruisdael, painting a country scene as if it were the backdrop for a Greek drama, or you could adopt the role of a draughtsman and produce factual, topographic pictures of patrons’ estates.

What you simply could not do was to present a picture of the English countryside as a picture of the English countryside. It simply wasn’t done.

All that started to change at the end of the eighteenth century when Sir Uvedale Price and Rev. William Gilpin started to publish their theories of the ‘Picturesque’. They told their readers, including the young Nursey, that the countryside complete with the all the haphazard influences of rural life, was beautiful in itself.The first painter who took these ideas to heart and made a big impression with them was John Constable (1776-1837). Troubled over an early attempt at painting the cottage of a man called Willy Lott, Constable was glad to receive a visit from his friend Perry Nursey. ‘It promises well’, Nursey told him. Encouraged, Constable persisted. The cottage became the backdrop for The Haywain.

Like both Constable and Gainsborough, Nursey was a Suffolk lad. Like them too, his desire to paint landscapes came direct from the Suffolk countryside around him. Trained to follow his father John Nursey as a country surgeon, he opted instead for the life of a professional painter, gaining tuition in Edinburgh under the great Scottish landscape artist Alexander Nasmyth (1758-1840). Returning to Suffolk, he met and fell in love with a young heiress, Anne Simpson. Probably acting on a romantic suggestion from his friends in Edinburgh – who may have included the likes of Sir Walter Scott and Robbie Burns – he ran away back to Scotland with Anne, where they married in 1795.

Thanks to Anne, Nursey suddenly became a man of means. Initially at least, however, he remained determined to make his own name as a professional painter. The couple moved to London and, from 1799 to 1802, he exhibited four landscapes at the Royal Academy, two of grandiose Italian and Scottish scenes, and two of his beloved Suffolk countryside.

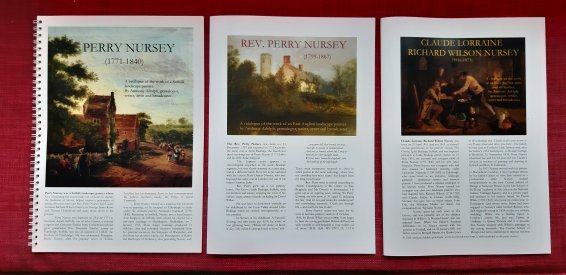

After London, they settled at Little Bealings near Woodbridge, part of Anne’s Suffolk inheritance. Nursey rebuilt her old farm house, creating a stylishly modern mansion called ‘The Grove’. Impressed with his work, members of the neighbouring gentry started commissioning him to redesign other Suffolk mansions, probably including Theberton House and Witnesham Hall.

[PN72] The Grove, Little Bealings, from an old lithograph, probably taken from an original painting by Perry Nursey himself.

Amongst the new, gentlemanly activities in which Nursey indulged was the co-directorship of Nacton Workhouse. Like everything else he did, he pursued his care of the poor with élan. He felt passionately that needy paupers should receive poor-relief in their own parishes, rather than being forced into workhouses. In a detailed letter to The Ipswich Journal on 24 May 1826, Nursey argued that maintaining a workhouse inmate cost an average of £9 a year more than if they were supported in their own homes. Further, being allowed to stay at home saved people from the degrading effect which the workhouse system had on their ‘energies and principles of independence, as well as the natural ties of feeling and affection’ when couples were separated from each other and from their children.

PN26. Perry Nursey, ‘Wilford Bridge’, Suffolk, with Woodbridge and the River Deben in the distance

At ‘The Grove’ Nursey entertained a stream of guests with open-handed friendship. They included co-directors of the workhouse and neighbouring gentry, but the most favoured guests were those who, like him, brimmed over with enthusiasm for Picturesque art. The landscape painters George James Rowe and Thomas Churchyard, the Quaker poet Bernard Barton and Edward FitzGerald, translator of the Rubáyat of Omar Khayyám – all of them local men (and the latter three later known as three of ‘the Woodbridge Wits’). From further afield came the Scottish landscape and portrait painter Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841), later portrait painter to the Royal Family, who painted several pictures of the growing Nursey family.

Perry and Anne Nursey had eleven children- and the first thing on their curriculum was painting. Two sons, Rev. Perry Nursey (1799-1867) and Claude Lorraine Richard Wilson Nursey (1816-1873), who was named after two of his father’s favourite landscape painters, became moderately successful artists in their own right, the latter founding the Leeds and Bradford schools of art. The eldest son, Robert, was engaged to Sir David Wilkie’s sister Helen, but he died, tragically young, just before the wedding.

In 1815, Wilkie painted a study of Nursey’s three youngest daughters which included an extra sketch of little Rosalba sitting by a pond, watching a kingfisher flashing past. The canny Scotsman may have been unaware at the time of the little bird’s symbolic meaning, for the kingfisher is the Halcyon bird, epitomising tranquility amidst the world’s storms. Whilst Perry Nursey reveled in his new, gentrified life at ‘The Grove’, his enthusiasm for selling his own paintings was waning before his desire to collect the beautiful – and expensive – works of others. Meanwhile, in the countryside he loved to paint, the agricultural depression was eating away at the value of his grain and of the wool from his flock of black Norfolk sheep. A rhyme published in William Hone’s Table Book of 1827 summed up the predicament of Perry Nursey, and many other gentleman farmers of the time, perfectly:

1722

Man, to the plough;

Wife, to the cow;

Girl, to the yarn,

Boy, to the barn;

And your rent will be netted.

1822

Man, Tally Ho:

Miss, piano;

Wife, silk and satin;

Boy, Greek and Latin,

And you`ll be Gazetted.

‘Gazetted’ refers to the bankruptcy notices which appeared every week in the London Gazette. In 1827, shocked by a review of his precarious finances, Nursey was forced to sell his beloved Grove, and was then obliged to obtain was a commission to redesign it for its new owner, James Colvin.

PN29. Perry Nursey, ‘Woodbridge Church and Abbey’, Suffolk

Nursey had staved off disaster but, having gained his place amongst the local gentry, he found it impossible to bow-out gracefully. First he rented Foxhall House, on the sandy heath between Woodbridge and Ipswich. Then in 1831 he moved his family to Foxburrow Hall, Melton, a house which he had designed for its Quaker owner William Whincopp (1795-1874). Desperate for funds, he won a few landscaping commissions and tried to sell drawings of Suffolk scenes.

PN19. Perry Nursey, rustic man and boy.

It was not nearly enough. At Christmas 1833 the sixty-two year old Nursey had the chilling experience of being ‘Gazetted’ for bankruptcy. The following spring everything he owned was auctioned, including the remainder of Anne’s inherited land, the Misses’ piano, his art collection and, worst of all, his own paintings. Edward FitzGerald let the devastated family stay at Boulge Cottage, Bredfield. Nursey tried to earn a living as an art teacher but his energy was spent. The family moved to an obscure house in Broadley Terrace, Paddington, where he died on 12 January 1840. He is buried not far away at Kensal Green cemetery.

Throughout his life, Perry Nursey never faltered in his passion for landscape painting. In Outlines in Lithography (1840), Dawson Turner wrote of Nursey’s ‘enthusiastic love for the art, that I have seldom, if ever, known exceeded’. Nursey believed strongly in painting in the open air, something which seems obvious now but which was avant garde in his day. Gainsborough, who loved hauling boulders and branches into his studio, would not have dreamed of setting up his easel in the open air. Indeed, anyone who has tried to do so will know what an awkward procedure it can be, with flies and seeds smudging the wet paint on sunny days and drizzle and wind interfering the rest of the time.

Nursey, like Constable and their younger contemporaries Churchyard and Rowe, however, loved the freshness of Nature and were prepared to put up with all discomforts in order to infuse their work with the quality of the open air. ‘There is a genuine feeling of Nature in one of Nursey’s sketches’, an enthusiastic FitzGerald wrote in 1838, ‘as in the Rubenses and Claudes here [in London]: and if that is evident, and serves to cherish and rekindle one’s own sympathy with the world about one, the great end is accomplished’.

PN7. Perry Nursey, ‘Woodbridge Abbey and the gates of St Mary’s Church’.

Nursey’s sketches also retain a remarkable vitality. His fluid right-handed pen-strokes, squiggles and dashes capture the old walls and trees in front of Woodbridge Abbey and remain as alive today as they were he sat down to draw the scene in the 1820s.

Nursey passed on his love of the Picturesque to his sons, Rev. Perry Nursey and Claude Lorraine Richard Wilson Nursey, and also to his Woodbridge protégés Thomas Churchyard (1798-1865) and George James Rowe (1804-1883), whose works, along with Constable’s, perpetuated Perry Nursey’s passionate love of the English landscape into the Victorian era.

NOTICE: To the Nobility, Gentry and all Persons of Discernment and Taste and Lovers of the Fine Arts, Mr Anthony Adolph of Mole Cottage, Beckenham in the County of Kent, Genealogist, Writer, Broadcaster and Artist, begs Leave to Announce the Publication of his New Catalogue of the Artistic Works of his late esteemed Ancestor Perry Nursey Esq., late of The Grove, Little Bealings in the County of Suffolk, Fully Illustrated in the new Colour Photography and each Work Numbered according to Mr Adolph’s New System of Classification. Copies of this Unique and Rare Publication may be had at the Modest Price of Fifteen Pounds apiece by application to the Author or at Mr John Day’s East Anglian Traditional Art Centre in Wickham Market in the County of Suffolk.

(C) Copyright Anthony Adolph 2019